Here and There

After an hour rumbling through the twists and turns of the Mauritian countryside, we piled out of our bus in front of the Intercontinental Slavery Museum. Immediately, I was struck by the architectural similarities between the museum—a former French hospital built by enslaved Mauritians—and Gorée Island off the coast of Dakar, Senegal. Gorée, which is only reachable from Dakar’s port by ferry (or the annual open-water swimming contest), is a small island filled with stately, colorful colonial homes that do not suggest its tragic history.

These days, Gorée Island hosts several museums as well as the renowned Door of No Return, which symbolizes enslaved Africans’ last steps before the brutal, often deadly transatlantic journey to North America. While Mauritius is geographically distant from Senegal, each functioned as an important hub for the chattel slave trade—a history that is reflected in the similarities between the museums in Dakar and Port Louis. In each context, former colonial buildings that once channeled trafficked human beings now serve as museums. However, while Senegal was a point of departure for enslaved Africans, Mauritius was a destination. As a result, museums in either country take markedly different approaches to slavery and its impact on culture, economics, and politics.

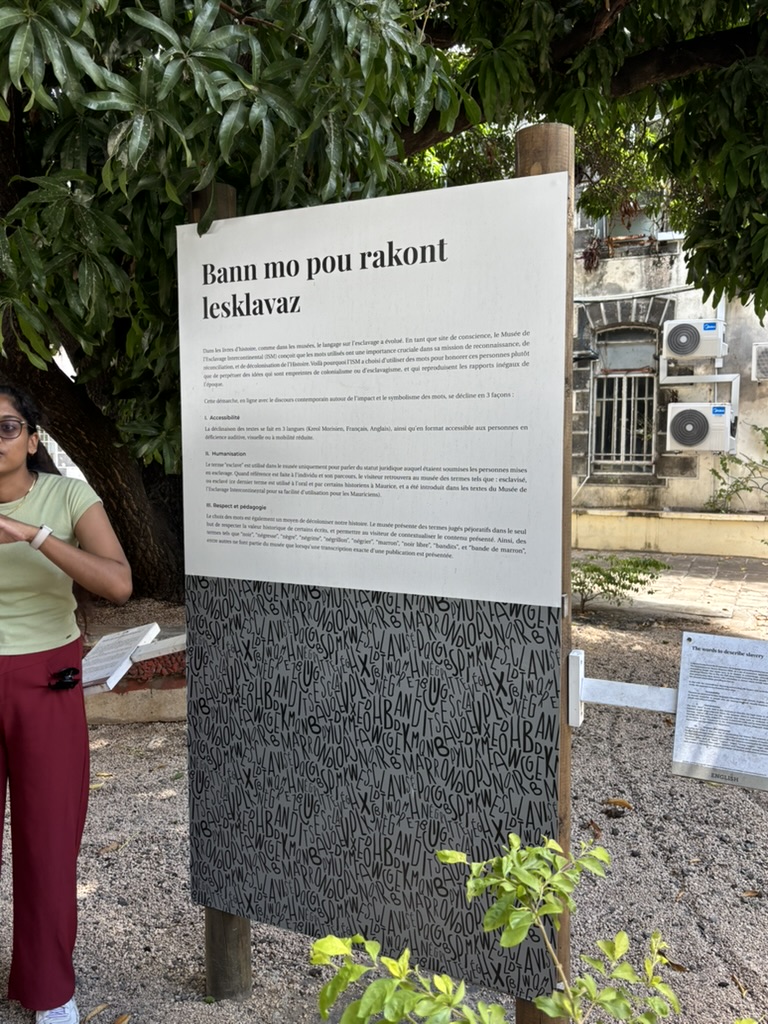

As I recall the extensive effort made on Gorée and around Dakar to document African culture that persisted in the face of centuries of slavery, I couldn’t help but notice the contrast with the Intercontinental Slavery Museum in Port Louis. Several classmates remarked that it felt as though the link between Africa and slavery on Mauritius had been glossed over at the museum. Indeed, Mauritian historians and public figures place great importance on the so-called Rainbow Island’s cultural syncretism: Indo-Mauritians, Mauritian Creoles, Sino-Mauritius, and Franco-Mauritians living together peacefully. However, it felt as though this emphasis came at the expense of centering the enslaved African experience in Mauritius.

This contrast continued to crystallize as we toured the Aapravasi Ghat harbor, now a UNESCO World Heritage Site that once functioned as an immigration entry point similar to Ellis Island. We learned that following the abolition of the slave trade, Great Britain used Mauritius to test its so-called Great Experiment—referred to today as indentured servitude. Almost immediately, ships from India began to arrive with indentured laborers whose presence transformed the Mauritian social and cultural fabrics.

Aapravasi Ghat itself closely documents this history without touching on the context that preceded Indian migration to Mauritius. Despite sharing much in common with formerly enslaved Africans—not the least of which was inhumane working conditions—Indians retained many of their ethnic, economic, and religious identities that helped form Mauritian communities with strong ties to the subcontinent. Conversely, Africans were stripped of their identities and thus faced a disadvantage as they sought to form sustainable, enduring communities. Perhaps a lingering impact of this structural issue is the difficulties that arise in attempting to tell African stories in present-day Mauritius. To that end, it is of note that the central source of the Intercontinental Slavery Museum’s exhibit on African slaves was an aristocratic Frenchman who did not outwardly oppose the slave trade. While there are no easy answers to these complicated questions, they nonetheless merit our best efforts.